By Cherise Fong

For CNN

(CNN) -- It's called "The Internet of Things" -- at least for now. It refers to an imminent world where physical objects and beings, as well as virtual data and environments, all live and interact with each other in the same space and time. In short, everything is interconnected.

Violet's Mir:ror reads information and instructions stored on Nano:ztags containing RFID chips.

"The Internet of the future will be suffused with software, information, data archives, and populated with devices, appliances, and people who are interacting with and through this rich fabric."

At the nodes of this all-encompassing web of objects is RFID (Radio Frequency Identity) technology, which allows things to be "read" by an NFC (Near Field Communication) scanner, bar-code-style, as well as to store information about themselves and their relationship with their environment, over time.

The reason why RFID is often called next-generation bar code is that the technology is more accurate, scanners can read more objects with less directional contact, and smaller chips can contain a larger quantity of information.

Bruce Sterling, one of the pioneers of cyberpunk literature in the 1980s and an active sci-fi guru, neologized the term "spime" in 2004 to refer to any object that can define itself in terms of both space and time, i.e. using GPS to locate itself and RFID to trace its own history.

"Whatever a Web page can do, so can a pair of shoes," says rafi Haladjian, the visionary co-founder of Violet.

So, in this case, can a rabbit.

In 2005, Violet launched the best-selling Nabaztag, a screenless, WiFi-enabled bunny, born again with voice-recognition and RFID-awareness in 2007. Interfacing the node between virtual data and the sensory world, Nabaztag fetches information from the Internet, flashes lights on its nose and tummy, rotates its ears, sniffs RFID chips, speaks 36 languages and understands five.

Last but not least, all the Nabaztag rabbits are interconnected, so you can even send one an e-mail.

In a similar but less eccentric initiative to bring the wonder of the Web out of the PC, the California-based start-up Chumby Industries launched the soft leather-cased Chumby, an alarm-clock-inspired device equipped with a motion sensor and dominated by a touch screen, in February 2008.

Based on the concept of customizable, automated, streaming widgets, Chumby partners with media services and social networks, as well as allowing user-created applications.

"Toys for hackers or a real business opportunity?"

Taking the interconnection of things outside the home and into the urban environment, Pachube functions like a virtual switchboard using EEML (Extended Environments Markup Language) to link buildings to architecture software to installations to artists' laptops to weather sensors to Second Life and beyond, all in real time.

"The distinction between 'real' and 'virtual' is becoming as quaint as the 19th century distinction between 'mind' and 'body,'" says Usman Haque, Pachube's creative director. "We want to bring about a connectivity between the physical world, its objects and spaces, and the virtual world of Web sites and environments."

Still in beta-testing, Pachube currently connects some 150 input and output feeds, including a Geiger counter measuring radiation in Japan, a ship in the Pacific, air quality in Beijing, Tower Bridge in London, and the location of an iPhone as it moves around the world.

Such is the novelty of these tangible nodes that the 2008 Picnic conference, which took place in Amsterdam on September 28, subtitled its topic on the Internet of Things: "Toys for hackers or a real business opportunity?"

At least 27 companies (including Cisco, Ericsson and Sun Microsystems) who in September 2008 founded the IPSO Alliance to promote the use of Internet Protocol for Smart Objects, seem to think it's the latter.

The Alliance will perform interoperability tests, document the use of new IP-based technologies, conduct marketing activities and advocate how networks of objects of all types have the potential to be converged onto IP.

Meanwhile, everyday applications of RFID are hardly lacking.

Transport passes are the most common, as a quick and coinless way to turn the stiles: London's Oyster card lets holders whiz through the tube; Hong Kong's Octopus card can be used for admission on anything from the tram to the fast-food restaurant to the swimming pool and horse-racing track; Japan's Suica card has since been adapted for mobile phones, so that commuters can simply swipe their handsets.

RFID tagging has also been widely used for such commodities as passports, access control, luggage tracking, store inventory, pets -- and yes, even people.

Just as a precious piece of artwork might be RFID-tagged to track its progress through a traveling auction, a hospital patient with Alzheimer's disease might have a microchip embedded under his skin so that he can be located and identified in case he gets lost. This method has also been used to keep tabs on inmates and individuals under house arrest.

Of course, the controversial issue of privacy already looms heavily over the potential mass proliferation of RFID tags in consumer goods, let alone under human skin.

But with every power comes responsibility. Perhaps one way of winning over the skeptics is to empower them with the tools to embrace the technology on an individual, highly personalized level.

"He who connects an egg, connects a cow"

"The Internet of Things begins with small things," advances Violet's Haladjian, "things that are fun, simple, accessible, and that people want to have at home because they are just as fun as they are practical.

"Little by little, they get used to this kind of object, learn how to use it, discover their limits as well as new opportunities. I really don't think the Internet of Things could have started with the smart refrigerator."

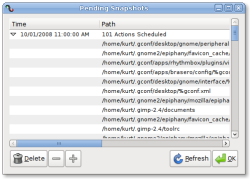

Shortly after Tikitag launched the first do-it-yourself RFID kit (consisting of a plastic plug-and-play NFC reader and a pack of 10 RFID sticker tags for $49.95) in October 2008, Violet announced Mir:ror, its own RFID starter package, made of mnemnotechnically metaphoric elements.

While Nabaztag pulled the white rabbits out of the holes, Mir:ror absorbs tagged objects through the looking glass and into the ever-expanding Internet of Things. Violet's RFID stickers are called ztamps and are supplemented by Nano:ztag mini-rabbits, which function as discrete programmable objects that trigger the action when they hop over the magic disk.

Telling these RFID devices what to do is child's play through user-friendly interfaces on the makers' respective Web sites. However both Tikitag and Violet have opened their sources to invite developers to contribute their own applications to the candy store. Meanwhile, ideas are brewing in the forums.

Conversely, as a growing number of mobile phones are equipped with NFC readers, people just may get into the habit of scanning every smart object out there.

For example, online versions of print magazines on newsstands could be called up for browsing, the legend for an artwork in a museum could give background and context, a poster for a concert could link to online ticket sales, a tactical interface could give oral directions to a blind person, an entire city could be tagged for an animated guided tour.

"We are still living in a world where information is trapped in a few of our objects," says Haladjian. "We stare into our screens, which are like goldfish bowls full of information swimming around, but unable to escape.

"At Violet, we dream of a world where information would be a butterfly, flitting freely all over the place, and occasionally landing on any of the objects we touch to give them life and enrich them."

After all, one of the most fascinating pre-incarnations of the Internet of Things is Boredomresearch's

RealSnailMail, in which e-mail messages interrupt their regularly scheduled path at the speed of fiber optics to be delivered across a 50-centimeter enclosure via RFID-equipped carrier snails.

Original here

When security in your underground base has been breached and you are about to be overrun, what's the last line of defense? It's a device called a Fast-Rising B Plug. And wannabe Bond villains inspired by the new movie should take note.

When security in your underground base has been breached and you are about to be overrun, what's the last line of defense? It's a device called a Fast-Rising B Plug. And wannabe Bond villains inspired by the new movie should take note.  Normally the B-plug is raised, and the silo is secure. But if a maintenance crew is inside, the B-Plug is lowered and — in theory — the bad guys could seize the opportunity and swarm in. This is why you need the fast-rising kit.

Normally the B-plug is raised, and the silo is secure. But if a maintenance crew is inside, the B-Plug is lowered and — in theory — the bad guys could seize the opportunity and swarm in. This is why you need the fast-rising kit.  During her years at CNET News, Ina Fried has changed beats several times, changed genders once, and covered both of the Pirates of Silicon Valley. These days, most of her attention is focused on Microsoft.

During her years at CNET News, Ina Fried has changed beats several times, changed genders once, and covered both of the Pirates of Silicon Valley. These days, most of her attention is focused on Microsoft.