The UK today cleared Google's Street View service for use after looking into the privacy implications of the program, but the panoramic pics of real-world streets and homes continue to generate controversy. Google's response to critics? Get over yourselves.

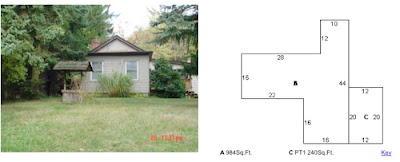

A Pittsburgh couple, Aaron and Christine Boring, sued Google earlier this year in federal court after their $163,000 home appeared on Street View; the shot of the home was allegedly taken from the couple's private road. How do we know the home cost $163,000? Because photos of the property, details of the sale, and even a rough floorplan are already publicly available on the Internet from the Allegheny County assessor (not linked to preserve whatever privacy the Borings have left).

Google's lawyers, not one to miss a trick, have already pointed this out the court. The couple claims injury "even though similar photos of their home were already publicly available on the Internet, and even though they drew exponentially greater attention to the images in question by filing and publicizing this suit while choosing not to remove the images of their property from the Street View service," says Google.

This statement is made in service of Google's larger point, which is: no one today has complete privacy. Except, perhaps, hermits.

"Today's satellite-image technology means that even in today's desert," Google writes, "complete privacy does not exist. In any event, Plaintiffs live far from the desert and are far from hermits... In today's society people drive on our driveways and approach our homes for all sorts of reasons—to make deliveries, to sell merchandise and services door-to-door, to turn around. As a society, we accept these 'intrusions'. They are customary, even expected." (The Smoking Gun unearthed the filing yesterday, though there's nothing "smoking" about it; anyone with PACER access to federal court cases can search for case 2:08-cv-00694-ARH.)

The pictures in question were "unremarkable photos" and the alleged trespass was "trivial." At every point in its response, Google passes off the complaints over Street View as simply too petty too bother with—even as it admits that its driver may, in fact, have driven past a sign marked "private road" to take the photo.

You complain, we fix

The company's point about complete privacy is well taken; we don't have it. But Google's preferred solution to the problem is for people to use "the simple removal option Google affords." Sound familiar? Sure it does, because it's the exact same argument the company uses against all rightsholders: tell us where the problem is, we'll fix it, but don't ask us to be proactive about clearing permissions first.

This dispute is at the heart of the Viacom/YouTube $1 billion lawsuit, among other cases. In this instance, Google basically says that it's up to people to scan Street View themselves, pick out photos that might be private, then notify the company. Staying off of private roads isn't Google's problem; it's the homeowner's.That might sound burdensome, but it's the same argument deployed against rightsholders over video.

This fundamental tension between the opt-in/get-permission/check-first model and the opt-out/seek-forgiveness/fix-later approach is shaping up as a fundamental point of contention on the Internet. NebuAd's opt-out approach to grabbing ISP clickstream data has become such a big deal that Congress has already held multiple hearings on the matter and has ISPs across the country running scared. When it comes to copyright, rightsholders have pushed (with some success) for video-sharing sites to screen uploaded content for possible violations before it goes live. User-generated content sites, which have powered the Web 2.0 revolution, are under attack over uploads of child pornography, regular pornography, and clips of public harassment and abuse of others. And a UK government commission this week recommended that user-generated content sites be forced to screen all uploads with human eyes before pushing them out to the web.

Copyright, privacy, and school bullying videos might not seem to have much in common, but the debate over screening first vs. fixing later could reshape the Internet as we know it. Having to get permission or screen content would hobble useful services like Street View and YouTube, and it would probably put companies like NebuAd out of business, even as it might lead to less objectionable or private content online.

But Wikipedia, YouTube, Flickr, and other services have shown us that the great mass of Internet users can produce a volume of content that boggles the mind and overwhelms attempts at centralized corporate screening and control.

Which approach do we want, and for which services do we want it? The Boring case is one tiny piece of this much larger debate, a debate which is about as interesting—and important—as Internet debates can be.

No comments:

Post a Comment